In a significant move underscoring the global scalability of “India-first” innovations, Google has announced the expansion of its foundational AI models for agriculture to the wider Asia-Pacific region. The Agricultural Landscape Understanding (ALU) and Agricultural Monitoring and Event Detection (AMED) APIs—already empowering startups and government agencies across India—will now be available to trusted testers in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Japan.

These freely available APIs leverage remote sensing and machine learning to deliver hyperlocal agricultural insights, tackling some of the most deep-rooted challenges in global farming. To understand the technology, its impact, and the vision behind this expansion, we spoke with Alok Talekar, Lead for Agriculture and Sustainability Research at Google DeepMind, and Avneet Singh, Product Manager with Google’s Partner Innovation team.

The Challenge: Fragmented and Data-Poor Farming Ecosystems

Agriculture in India—and much of Asia—is a complex, fragmented landscape where solutions that succeed in one region often fail in another. This lack of granular, field-level data has long been a barrier to progress.

“Largely, everybody wants to do the right thing, but agriculture is very diverse in the country,” said Talekar. “They just don’t have the right tools and access to information.”

According to Singh, most existing data is aggregated at district or block levels—far too coarse for precision farming. “The right intervention is needed at an individual field level,” he explained. “That’s the gap we’re hoping to address.”

Without this granularity, decision-making remains blunt. As Talekar put it, “The answer that’s true in Kerala may not be true in Bihar or Vietnam. You need local decisions backed by robust data that enables data-driven action.”

The Solution: Foundational AI Models for a Digital Harvest

Rather than building consumer-facing apps, Google has created foundational models—a digital infrastructure layer for an entire ecosystem to innovate on.

Agricultural Landscape Understanding (ALU)

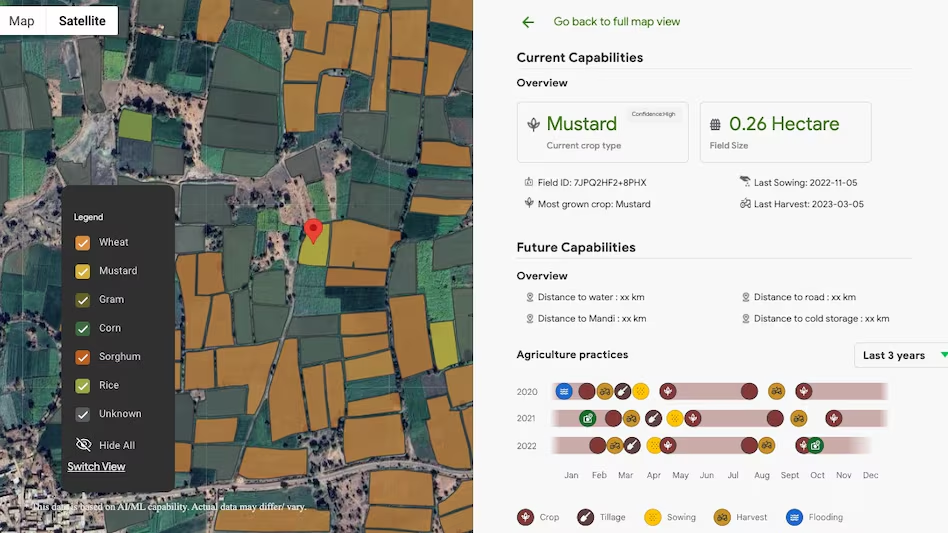

Launched in India in October 2024, ALU segments the agricultural landscape using satellite imagery, identifying individual field boundaries, vegetation, and water bodies. “It’s our effort at digitally mapping the agricultural landscape,” Singh explained.

Agricultural Monitoring and Event Detection (AMED)

Introduced in July 2025, AMED builds on ALU by offering dynamic, near real-time field-level insights. “We start looking at what’s happening at an individual field,” Singh said. The model identifies crop types, acreage, and key events such as sowing and harvesting, with updates every 15 days.

Together, these APIs unlock an unprecedented, unbiased agricultural dataset. “We are unlocking a flood of data that was previously unavailable,” said Talekar. “This is the beginning of a journey where partners can start building transformative solutions on top of it.”

The Technology: Data Depth and Accuracy

These AI models rely heavily on geospatial data, primarily from public and licensed satellite imagery. Google’s decades-long investment in Google Maps and Earth Engine gives it a unique edge in large-scale earth observation.

However, Talekar acknowledged the inevitable challenge of accuracy at scale. “Any model working at this magnitude won’t be perfect everywhere,” he said. “The key question is: what level of statistical accuracy makes it useful for a given use case?”

To ensure reliability, Google applies multi-layered validation—including standard ML checks, comparison with official census data, and third-party audits by partners like TerraStack and the Government of Telangana.

Real-World Impact: From Crop Yields to Credit Access

While most farmers may never directly interact with these APIs, their benefits reach them through an ecosystem of AgriTech partners.

For example, a startup focused on crop optimization can use ALU and AMED to identify crop types and sowing patterns across thousands of fields—then deliver targeted advice to farmers in near real time.

But the most profound impact may come from financial inclusion. As Talekar explained, many farmers struggle to access formal credit because banks find field verification costly. “The cost of sending someone to verify a loan applicant’s crop is often comparable to the loan size itself,” he said.

With Google’s models providing verifiable, low-cost digital evidence of farming activity, lenders can assess risk more efficiently. In India, fintech firm Sugee.io is already using the APIs to improve loan processing and management, potentially unlocking fairer credit access for millions of smallholders.

An Ecosystem in Bloom

In India, Google’s agricultural models are already integrated into multiple flagship initiatives:

Krishi DSS – A national decision-support platform for the Department of Agriculture.

AdEx (Telangana) – The state’s open data exchange for agricultural applications.

CEEW – A think tank leveraging the data for differentiated income support to promote climate-resilient crops.

Global Vision, Local Roots

The success of this ecosystem-led model in India has encouraged Google to scale it across Asia-Pacific. “We’re excited and hopeful that expanding these APIs across APAC will unlock similar impact,” said Talekar. “It reaffirms our conviction that solutions built for India’s most pressing challenges can help solve for the world.”

Singh emphasized that privacy remains a core design principle. “All data is geospatial—there’s no personally identifiable information,” he assured. “There’s no ownership construct within this. Farmer privacy is protected.”

Recent Random Post: