The Great Indian Election circus has just begun.

The Great Indian Election circus has just begun.

So far, we have seen two phases of the elections in different states. The Big Bang of the election is Prime Minister Narendra Modi. For the opposition, he is the main agenda, how does one oust him in order to get the throne in South Block back. For the ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the issue is also Modi. He remains the brand equity of the party.

The Sangh Parivar votebank argues that Modi is the victim. Lutyens’ Delhi doesn’t like him, as he isn’t elitist. Modi wants to break away from the status quo of Delhi’s ancient political corruption. The BJP clientele remains active in supporting him. It is Modi around whom the main polarisation is taking place. The so-called Left Liberal public intellectual, and the secular civil society remain highly intolerant regarding the intolerance of the Modi-era. On the other hand, the BJP thinks that in all the seats in the country, where the BJP is contesting, it is Modi who is contesting.

In Indian politics, this extreme either-or situation has ironically happened only in the last few decades. That is, with Mrs Indira Gandhi. The Congress campaigned for her, with their slogan of ‘garibi hatao’ and it was the Left which was the demon. This ademonology’, this politics of aothering’, isn’t new in India. It is like the pendulum of an old clock. It swings to one extreme, before moving to the other. It was anti-Congressism in 1967, reaching its extreme in 1989. Then, the BJP took the Congress space and the anti-BJPism started in full swing when Vajpayee was the PM.

The Modi-era is a new phenomenon. The idea: a strong leader, with strong Hindu nationalism to back him, supported by a strong economy. In spite of all discontent, one has to accept that the economic conditions appear favourable to rapid growth in the country. The market has sensed it today, signs of upward movement in the market are there and the scene of market inflow seems positive.

It remains a fact that while travelling in different villages in the country, several of Modi government’s schemes – Swacch Bharat, LPG supply to rural areas, housing programmes, Modi’s health care programme, the opening of Jan Dhan accounts – have all had a positive impact on the lives of the poor. These aren’t very exciting hot potatoes for us in the media – but the actual beneficiaries might have a different reaction.

Sitting in Delhi, this, is something we might forget and fail to understand.

But it is also true that there is a strong sense of discontent in the urban populace over job creation. Price rise and unemployment have, like always, been the opposition’s weapons. Jawaharlal Nehru would write letters to all his chief ministers, from the early days of 1947 till the last day in office in 1964, that ’employment, poverty alleviation, price rise’ were the main challenges of the country. Over 70 years later, we are still fighting the issue and no one has figured out where the magic lantern remains hidden.

The anti-Pakistan Balakot strike did change the election narrative. Modi and BJP were aggressive on national security and on Hindu nationalism. The opposition became defensive. Rahul Gandhi’s Rafael issue became a non-starter. But after two phases of elections in Delhi, a lot of people asked me, “Is there a change in milieu? Is the nationalism plank down? Imran Khan said Modi should come to power, so they can start the dialogue. Did that spoil the BJP’s anti-Pakistan stand.”

Be that as it may, I think that in these elections it remains Advantage-Modi. There is no tsunami in favour of Modi, like what we’ve seen in 2014. But after completing two phases of elections, the unanswered question is still there: What is the alternative?

Rahul Gandhi got the opportunity and he started well. The 2014 perception of him was very different from earlier, when the BJP had campaigned successfully against him, rendering him a ‘pappu’. I took Rahul Gandhi’s interview in 2014 for Anandabazar Patrika. I found him to be intelligent and a thorough gentleman. Even he told me that he was fighting against a hologram created by Modi and the BJP. He was the general of the party, so he didn’t admit, but my impression through the conversation remained that he understood the situation and the fate of the 2014 polls before the results were announced.

This time he has been more serious, more deliberate. His interactions abroad also got him momentum. His image was calibrated away from what was, to a more serious general of a party. But then again, he has fallen into the old trap.

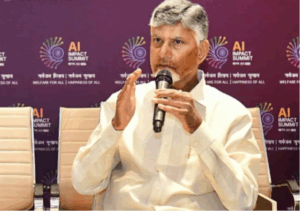

His main mistake was to not form an opposition-front before the election. Mamata Banerjee’s proposal was to form a loose federation. At the time, Rahul Gandhi ignored not just Mamata, but also Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal. Congress thought that the ‘Aklo Cholo (Go alone)’ policy’ would be more useful than a compromise formula with regional forces. Rahul Gandhi thought that an alliance with regional parties would be a liability. Congress may get more seats in the country if they don’t go for a new Federal Front like UPA III. Actually, this overconfidence of Rahul Gandhi will spoil the opposition unity index further. He got into an alliance with N. Chandrababu Naidu in Telangana, but this became counterproductive – its impact stretching to Andhra Pradesh.

The victories in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh assembly elections disturbed Rahul Gandhi’s long term strategy for 2019. In the Hindi-heartland, the Congress is in a sorry state: it is a poor No. 4. Ask Mayawati – the Congress is untouchable. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra landed with a message of sibling solidarity, but ask the local Congress worker, it is too little too late.

It is clear that in this election, it is not just Mamata-Mayawati-Akhilesh Yadav or even Tejashwi Yadav who are fighting against Narendra Modi. These regional leaders are giving it their all.

But where is the Congress? Where is Rahul Gandhi?

Recent Random Post: